One of the biggest mysteries in the history of beer concerns a drink called three-threads, and its exact place in the early history of porter. Three-threads was evidently a mixed beer sold in the alehouses of London in the time of the last Stuart monarchs, William III and his sister-in-law Anne, about 1690 to 1714. For more than 200 years, it has been linked with the development of porter: but the story that said porter was invented to replace three-threads was written eight decades and more after the events it claimed to record, and the description that the “replaced by porter” story gave of three-threads early in the 19th century does not match up with more contemporary accounts of the drink from the late 17th century.

One of the biggest mysteries in the history of beer concerns a drink called three-threads, and its exact place in the early history of porter. Three-threads was evidently a mixed beer sold in the alehouses of London in the time of the last Stuart monarchs, William III and his sister-in-law Anne, about 1690 to 1714. For more than 200 years, it has been linked with the development of porter: but the story that said porter was invented to replace three-threads was written eight decades and more after the events it claimed to record, and the description that the “replaced by porter” story gave of three-threads early in the 19th century does not match up with more contemporary accounts of the drink from the late 17th century.

So what exactly was three-threads? Well, I now believe that enough people have dug out enough information that we can make a firm and definitive statement on that.

It was a tax fiddle.

To understand what was going on, you need to know that from the time when taxes were first imposed on beer and ale, in 1643, during the English Civil War, and for the next 139 years the excise authorities recognised only two strength of beer and ale for tax purposes: “small”, defined as having a pre-tax value of six shillings a barrel, and “strong”, defined as having a value of more than 6s a barrel. To begin with, the tax represented only a tiny proportion of the retail cost, at less than a tenth of a penny a pint for strong drink and not even two tenths of a penny per gallon for the small stuff. But in 1689, when William III of the Netherlands and his cousin, wife and co-ruler Mary had arrived in Britain and pushed Mary’s father James II off the throne, the need to pay for the “war of the British succession” and the continuing Nine Years’ War against Louis XIV of France saw the duty on beer and ale bounced upwards, from two shillings and sixpence a barrel to 3s 3d. The following year, 1690, the tax was doubled, to 6s 6d a barrel on strong ale and beer, more than a farthing a pint, when strong liquor retailed at a penny-ha’penny a pint, or 3d a quart “pot”. The rise in the tax on small drink was proportionate, to 1s 6d a barrel, but still the total tax on small beer and ale equalled only a half-penny a gallon.

The flaw in the system was that extra-strong beer or ale paid the same tax as “ordinary” or “common” strong beer. Unscrupulous brewer, and retailers, could therefore – and did – take a barrel of extra-strong beer and two of small beer, on which a total of 7s 3d of tax had been paid, mix them to make three barrels each equal in strength to common strong beer, which should have paid tax of 14s 3d in total, and save themselves 2s 4d a barrel in tax. This may have been equal to only a fifth of a penny a pot, or thereabouts, but it was still 6% or so extra profit. (Incidentally, for those of you new to this, “ale” at the time meant a drink with less hops in, and generally stronger, than “beer”.)

The excise authorities were certainly wise to this fiddle, and laws banning the mixing of different strengths of worts or beers were passed by Parliament in 1663 and again in 1670-1, 1689, 1696-97 and 1702, with (in William III’s time) a fine of £5 per barrel so mixed. That certainly did not stop people. Some time between 1698 and 1713, on the internal evidence, a manuscript was written, now in the Lansdowne collection in the British Library, titled An account of the losse in the excise on beer and ale for severall yeares last paste, with meanes proposed for advanceing that revenue. It was probably produced by an anonymous Excise or Treasury official, because he had access to official tax data from 1683 to 1698, and it gives a fascinating account of the prices and likely strengths of beers and ales at the time. “Very Small Beer” retailed pre-tax at 3s a barrel, and paid (since 1693) 1s 3d a barrel tax. “Common Strong Beer and Ale”, made from “four Bushells of mault” – suggesting an original gravity of 1075 to 1085 – sold for 18s a Barrel and paid, at the time, 4s 9d a barrel tax. “Very Strong Beer or ale the Barrell being the Strong from 8 Bushells”, suggesting a huge original gravity, perhaps north of 1160, sold for £3 a barrel, but still paid the same 4s 9d a barrel tax as common strong beer or ale.

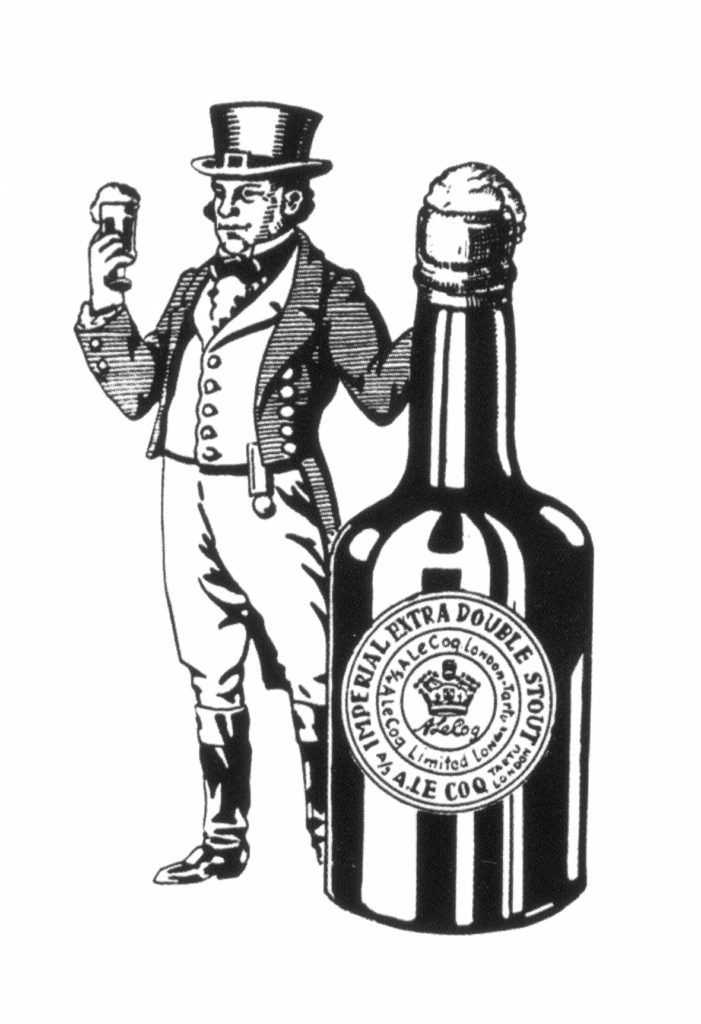

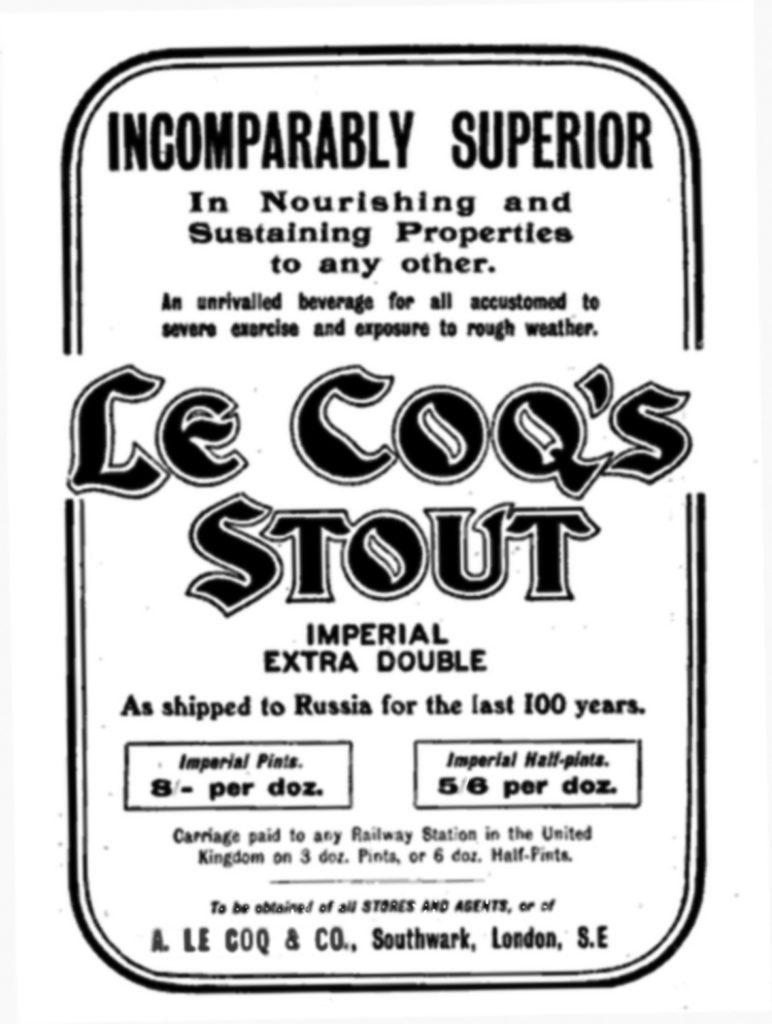

The fact that very strong brews paid the same tax as “common standard strong drinke” had “begot a kind of trade of Defrauding”, the anonymous author wrote, and he declared that “the notion thereof and Profitt thereby” of mixing very strong ale or beer with small beer and selling it as common strong ale or beer “has been of late & now is generally knowne”, and “the traders therein have turned themselves more and more to the practice of Brewing it,” “very strong Drinke being now Commonly a parte of the Brewers Guiles, and the whole of many who Brew nothing else.” The result, he said, was that “the Consumption of it is everywhere, which you have under several odd names, as Two Threades, 3 Threades, Stout or according as the Drinker will have it in price, from 3d. to 9d. the quarte.”

That “3 threades” was a mixture of ordinary small ale or beer and very strong beer is confirmed by a publication called The Dictionary of the Canting Crew by “BE” (the “canting crew” being those who spoke in “cant”, or slang), published around 1697/1699. This called three-threads “half common Ale and the rest Stout or Double Beer”: both “stout” and “double beer” meant “extra-strong beer”, while “common ale” was the same as table ale or small ale, and brewed at one and a half bushels of malt to the barrel, giving an OG of around 1045. Mix a beer that was perhaps 10 or 11 per cent alcohol by volume with one that was only 4.5 per cent or so, and you’ll have a beer of around 7.5 per cent or so, of course, about the same strength of common strong ale: but one that gave the retailer a better profit that “entire gyle” strong beer did, because it had paid less tax.

That “3 threades” was a mixture of ordinary small ale or beer and very strong beer is confirmed by a publication called The Dictionary of the Canting Crew by “BE” (the “canting crew” being those who spoke in “cant”, or slang), published around 1697/1699. This called three-threads “half common Ale and the rest Stout or Double Beer”: both “stout” and “double beer” meant “extra-strong beer”, while “common ale” was the same as table ale or small ale, and brewed at one and a half bushels of malt to the barrel, giving an OG of around 1045. Mix a beer that was perhaps 10 or 11 per cent alcohol by volume with one that was only 4.5 per cent or so, and you’ll have a beer of around 7.5 per cent or so, of course, about the same strength of common strong ale: but one that gave the retailer a better profit that “entire gyle” strong beer did, because it had paid less tax.

In 1697 a tax on malt was introduced alongside the taxes on the finished product, at the bizarre-looking rate of six pence and sixteen 21sts of a penny a bushel. (My best guess on that odd sum is that it works out to not quite 4s 6d a quarter – but six pence and five eighths of a penny a bushel is 4s 6d a quarter exactly, so why the approximately 2% difference? If anyone has a good answer to this conundrum, I’d be grateful …) For the first time, the country’s very large number of private household brewers had to pay tax, if they bought their malt from commercial maltsters, while brewers were also now paying more tax when they brewed extra strong beer than when they brewed “common” strong beer, because of the extra (taxed) malt used. But even on double beer at eight bushels to the barrel, that only came out to around three farthings per gallon more tax, and it failed to stop brewers continuing to cheat the revenue by mixing small drink with extra-strong. A disgruntled former General Surveyor of Excise, Edward Denneston, “Gent”, who had been involved in inspecting breweries since at least the early 1680s, wrote what amounted to a 40-page rant in 1713 with the unsnappy title A Scheme for Advancing and Improving the Ancient and Noble Revenue of Excise upon Beer, Ale and other Branches to the Great Advantage of Her Majesty and the general Good of her Subjects. It claimed that the brewing profession had become rich solely because of the “Frauds, Neglects and Abuses” practised by the brewers to the detriment of the country’s tax take. Brewers, he said, were “Vermine … that eat us up alive” and he told them he wished them “all boiled in your own brewing Cauldrons, or drowned in your own Gile Tunns”.

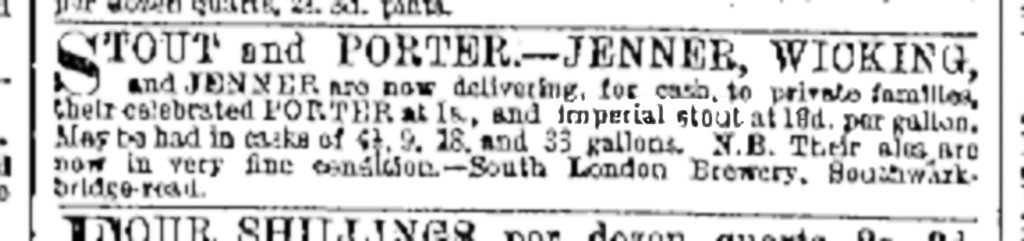

Denneston was a man with a grievance: he claimed that when he was a General Surveyor of Excise in London, he had spent several hundred pounds of his own money uncovering fiddles at the royal brewhouse in St Katharine’s, by the Tower, which brewed beer for the navy. One such fraud cost the government £18,000 a year, and he had been promised a reward by the House of Commons for stopping it, which, he said, he had never received. He also claimed that the country was losing £200,000 a year in unpaid tax – equivalent, in relative terms, to more than £4 billion today – because of the wider fiddles practised by brewers and publicans, and declared: “before there was a Duty of Excise laid upon Beer and Ale, it was not known any Brewer ever got so much by his Trade as what is now call’d a competent Estate; but since a Duty of Excise was laid upon Beer and Ale, nothing is more obvious, amazing and remarkable, than to see the great Estates many Brewers in and about the City of London have got, and are daily getting.” This, he said, was because “the Brewers in general, ever since there was a Duty upon Beer and Ale, have been more or less guilty of defrauding that Duty in several Methods,” including bribing the excise officers (in October 1708, “T– J–, Brewer” was put on trial at the Old Bailey for allegedly giving 40s a week to four officers of the excise to ignore his mixing of small beer with strong, though he was found not guilty), illegally brewing with molasses rather than malt , like the brewer “lately and remarkably in Southwark”, who was “fined several Hundred Pounds, for using of Molossas in his Beer and Ale”, and, in particular, avoiding the tax on strong beer and ale by mixing extra-strong drink with small.

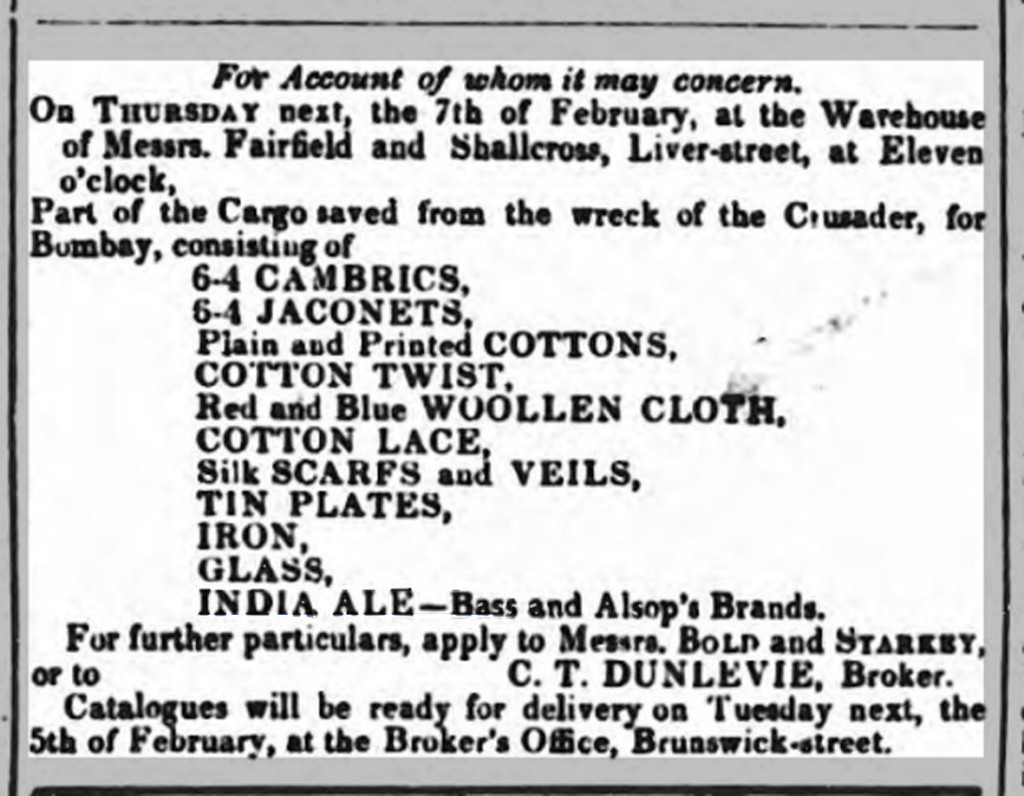

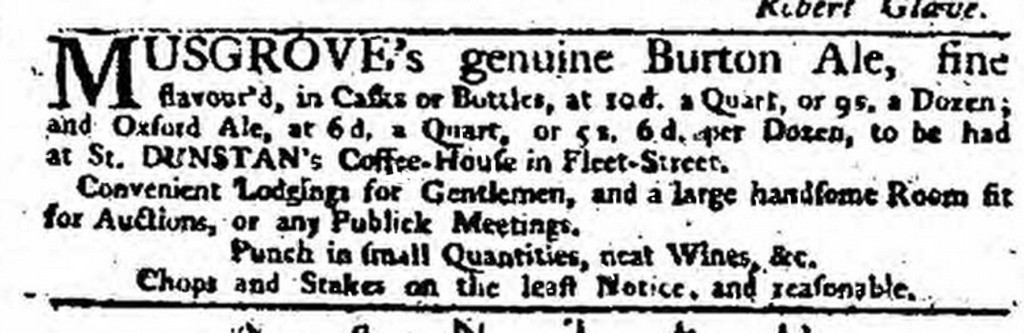

One such fiddle Denneston claimed to have uncovered when he was working for the Revenue in London as General Surveyor involved the publican at the Fortune of War in Well Close, Goodman’s Fields, just to the east of the Minories, and on the edge of the City. Denneston said that while visiting Well Close on official business, he spotted a sign outside the pub which said: “Here is to he Sold Two Thrids, Three Thrids, Four Thrids, and Six Thrids.” “My Curiosity up on this Subject, led me into the House,” Denneston said. “I call’d for my Host, desir’d to know what he meant by the several sorts of Thrids ? He answer’d, That the meaning was, Beer at Twopence, Threepence, Fourpence, and Sixpence a Pot, for that he had all sorts of Drink, and as good as any in England; upon which I tasted all the four sorts, and found they were all made up by Mixture, and not Beer intirely Brew’d ; upon which I order’d the Surveyor of that Division to go and search that House, where he found only two sorts of Drink, viz extraordinary Strong Beer, and Small, so that according to the Price he Mixt in Proportion; the same Fraud being more or less practis’d through the Kingdom.”

Denneston must have had an extraordinary palate to detect the difference between mixed beers and “intirely brewed” ones, but ignoring that, “Three Thrids” is obviously the same as three-threads, and Denneston confirms that it was a mixture of extra-strong beer and small beer, sold for three pence a pot, or quart, with two-threads costing two pence, four-threads costing four pence and so on. Why “threads”? One definition of “thread” is “a thin continuous stream of liquid”: the Elizabethan author Thomas Nashe wrote of “thrids of rayne”, while another writer in 1723 wrote of “fat Liquor” that when poured out would “go on in a long Thread whose Parts are uninterrupted”.

Three-threads is mentioned several more times during the 18th century, but by 1760 the practice of retailers mixing extra-strong and small beers and ales had evidently ceased, and “three-threads”, if talked about, had to be explained. In November that year a letter by someone calling himself “Obadiah Poundage” (“poundage” being another work for duty or tax) and claiming to be an 86-year-old clerk at one of the great London breweries, living at Newington Green, Islington, was published in the London Chronicle under the title “The History of the London Brewery since 1688” – “brewery” here being used in the sense “brewing trade”. Poundage was detailing the rise in the tax on beer and ale in the times of William III and Queen Anne, and how the brewers dealt with that. In a passage that was to become famous, he wrote: “Our tastes but slowly alter or reform. Some drank Mild Beer and Stale; others what was then called Three-threads, at 3d per quart; but many used all stale, at 4d per pot. On this footing stood the trade until about the year 1722, when the Brewers conceived there was a method to be found preferable to any of these extremes; that beer well brewed, kept its proper time, became racy and mellow, that is, neither new nor stale, such would recommend itself to the public. This they ventured to sell at 23s per barrel, that the victualler might retail it at 3d per quart. At first it was slow in making its way, but in the end the experiment succeeded beyond all expectation. The labouring people, porters etc. experienced its wholesomeness and utility, they assumed to themselves the use thereof, from whence it was called Porter or Entire Butt.” (“Stale”, here, incidentally, means “matured”, not “off”, and it was the opposite of “mild”, or fresh beer: a mixture of old, matured, sharp beer and fresh, sweet, new beer was a favourite with many drinkers through to the 19th century at least.)

This was the first time that three-threads had been linked with the birth of porter, albeit obliquely, and with the two drinks apparently having nothing in common except the fact that they both retailed at 3d a quart. Poundage’s words were quickly plagiarised – they were reprinted, without acknowledgement in The Gentleman’s Magazine the same month, and reappeared in various publications over the next 40-plus years. More recently the pot has been muddied by the former brewer HS “Stan” Corran, who wrote A History of Brewing in 1975 and seems to have had access to a different version of Poundage’s letter, because he printed a lengthy extract from it in his book in which the line “Some drank Mild Beer and Stale; others what was then called Three-threads, at 3d per quart” was replaced by “Some drank Mild Beer and Stale; others ale, mild beer and stale blended together [my emphasis] at 3d per quart.” Corran apparently found this alternative version in the archives of Guinness in Dublin: how it got there is not known and, alas, Guinness’s archivists cannot find it now. It has been suggested by James Sumner, to whom I am grateful for much of the research in this post, that it ended up in Dublin via the private papers of the 18th century Hampstead brewer Michael Combrune. If that alternative version, or another copy, was around at the end of the 18th century, it may have influenced what happened next in the narrative history of three-threads: because suddenly, decades after it disappeared, the drink was given a completely different description to the one Denneston gave it, and it was plugged firmly into the story of the development of porter.

This was the first time that three-threads had been linked with the birth of porter, albeit obliquely, and with the two drinks apparently having nothing in common except the fact that they both retailed at 3d a quart. Poundage’s words were quickly plagiarised – they were reprinted, without acknowledgement in The Gentleman’s Magazine the same month, and reappeared in various publications over the next 40-plus years. More recently the pot has been muddied by the former brewer HS “Stan” Corran, who wrote A History of Brewing in 1975 and seems to have had access to a different version of Poundage’s letter, because he printed a lengthy extract from it in his book in which the line “Some drank Mild Beer and Stale; others what was then called Three-threads, at 3d per quart” was replaced by “Some drank Mild Beer and Stale; others ale, mild beer and stale blended together [my emphasis] at 3d per quart.” Corran apparently found this alternative version in the archives of Guinness in Dublin: how it got there is not known and, alas, Guinness’s archivists cannot find it now. It has been suggested by James Sumner, to whom I am grateful for much of the research in this post, that it ended up in Dublin via the private papers of the 18th century Hampstead brewer Michael Combrune. If that alternative version, or another copy, was around at the end of the 18th century, it may have influenced what happened next in the narrative history of three-threads: because suddenly, decades after it disappeared, the drink was given a completely different description to the one Denneston gave it, and it was plugged firmly into the story of the development of porter.

Early in 1802 the Monthly Magazine printed a piece on the history of what was then easily London’s favourite beer which said: “The wholesome and excellent beverage of porter obtained its name about the year 1730 … [formerly] the malt-liquors in general use were ale, beer, and twopenny, and it was customary for the drinkers of malt-liquor to call for a pint or tankard of half-and-half, ie a half of ale and half of beer, a half of ale and half of twopenny, or a half of beer and half of twopenny. In course of time it also became the practice to call for a pint or tankard of three threads, meaning a third of ale, beer, and twopenny; and thus the publican had the trouble to go to three casks, and turn three cocks for a pint of liquor. To avoid this trouble and waste, a brewer, of the name of HARWOOD, conceived the idea of making a liquor which should partake of the united flavours of ale, beer, and twopennyy He did so and succeeded, calling it entire or entire butt, meaning that it was drawn entirely from one cask or butt; and as it was a very hearty nourishing liquor, it was very suitable for porters and other working people. Hence it obtained its name of porter.

There are many problems with that story: porter was actually first mentioned in 1721, and while Ralph and James Harwood were porter brewers in Shoreditch, theirs was a small concern compared to the giants such as Truman, Whitbread and Parsons, and there is no evidence from the preceding 80 years that they had anything to do with the development of the drink, apart from a couple of brief and obscure references which themselves said nothing about three-threads. Porter was indeed also known as “entire butt”, but not because it was a one-cask-only reproduction of a drink that had originally been served from three different casks. It was so called because it was brewed “entire”, the technical term at the time for a beer or ale made from a combination of all three mashes of the malt, instead of the first mash being used to make strong ale or beer and the others standard beer and small beer, as was usual, and it was then matured in butts, 108-gallon casks. There is no evidence at all that porter was brewed to replace three-threads; and most importantly to our story, the description of what three-threads was, a combination of ale, beer and “twopenny” from three casks, is totally at odds with what Denneston described being served at the Fortune of War nearly 90 years earlier under the name three thrids, a mixture of just two drinks, extra-strong and small. Just to undermine the Monthly Magazine‘s narrative some more, “twopenny” WAS ale, according to Obadiah Poundage in 1760, who described it as a pale ale retailed at four pence a quart, or two pence a pint, made by the London brewers in imitation of the beers the country gentry “residing in London more than they had in former times” were “habituated to” at home. So according to the Monthly Magazine, three-threads was a tautological mixture of ale, beer and ale – though, admittedly, if the second was pale ale, the first could have been brown ale.

Unfortunately, within a very short time the Monthly Magazine‘s version of history was being reprinted, first in a guidebook called The Picture of London, also published in 1802, and then dozens – hundreds – of times over the next two centuries. Occasionally there were variations: John Tuck, writing in 1822, in a book called The Private Brewer’s Guide to the Art of Brewing Ale, Stout and Porter, said that “a mixture of stale, mild and pale, which was called three-threads, was sold at four pence per quart as far back as 1720,” which, as we have seen, was wrong on both ingredients and price. But everywhere it became the accepted truth that three-threads was a mixture of three different drinks, and porter was brewed to replace it.

I hope I have shown that three-threads was not the drink the Monthly Magazine and almost every other writer on the subject from 1802 has said it was, and also that, fascinating though the story of three-threads is, it has nothing to do with the development of porter. If any beer did, in fact, it was the strong “twopenny” pale ale that the gentry brought a taste for to London. According to manuscript histories of the brewing trade written out by Michael Combrune in the 1760s, this pale ale became “spontaneously transparent” and the established London brown-beer brewers decided to try to match this by ageing their own product much longer than they had previously, adding more hops to help it keep. As it aged, it mellowed, and this mellow brown beer, “neither new nor stale”, as Poundage said, and retailing for 3d a quart, became the beer that porters quickly grew to love above all others.

I hope I have shown that three-threads was not the drink the Monthly Magazine and almost every other writer on the subject from 1802 has said it was, and also that, fascinating though the story of three-threads is, it has nothing to do with the development of porter. If any beer did, in fact, it was the strong “twopenny” pale ale that the gentry brought a taste for to London. According to manuscript histories of the brewing trade written out by Michael Combrune in the 1760s, this pale ale became “spontaneously transparent” and the established London brown-beer brewers decided to try to match this by ageing their own product much longer than they had previously, adding more hops to help it keep. As it aged, it mellowed, and this mellow brown beer, “neither new nor stale”, as Poundage said, and retailing for 3d a quart, became the beer that porters quickly grew to love above all others.

Not everybody will agree with me. John Krenzke, whose PhD dissertation on the industrialisation of the London beer trade 1400-1750 I have leaned on for much of the information to be found in this post, believes porter to have been brewed specifically to imitate the taste of three-threads. I have the greatest respect for John’s scholarship, which uncovered far more facts about the early history of three-threads than I was able to. But I cannot go along with his conclusion: I see no evidence that porter was anything other than an improved version of London brown beer, and that three-threads was something completely different. No writer until the Monthly Magazine in 1802, in a story demonstrably wrong in many ways, ever said porter was a replacement for three-threads. It looks like my journalistic ancestor missed the true, and much better story – that with every slurp, the three-threads drinker was diddling the tax man

Filed under: Beer, Beer myths, History of beer