![Guinness Yeast Extract Guinness on toast - nom]()

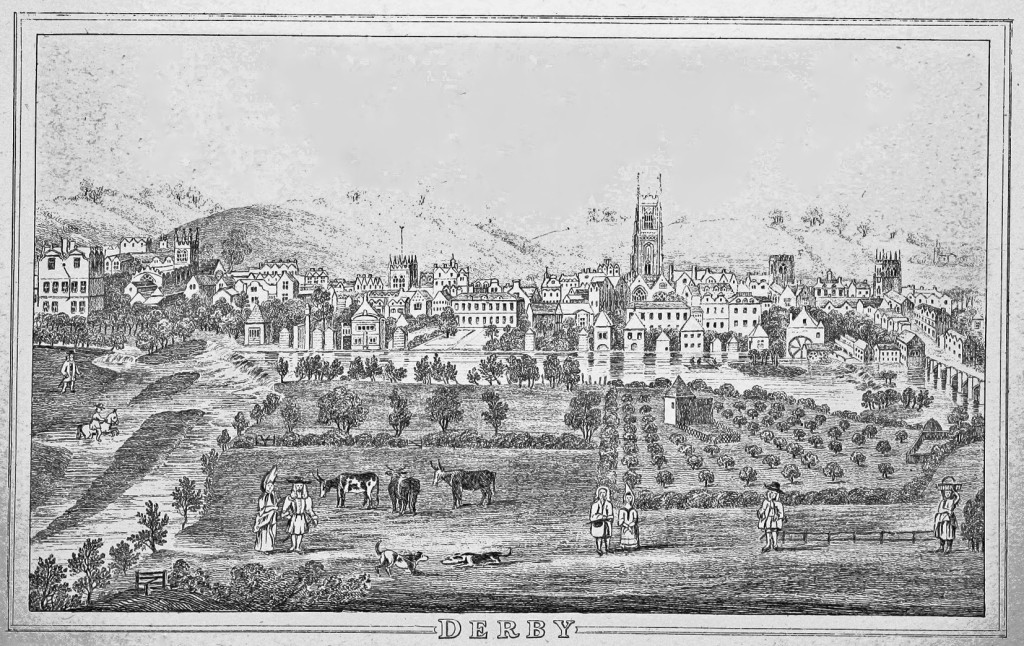

‘Guinness Marmite’ from the 1930s

Is there a brewery business with more books written about it – is there any business with more books written about it – than Guinness? Effectively a one-product operation, Guinness has inspired tens of millions of words. Without trying hard, I’ve managed to acquire 18 different books about Guinness, the brewery, the people, the product and/or the advertising (four of them written by people called Guinness), and that’s not counting the five editions I have of the lovely little handbook that Guinness used to give to visitors to the brewery at St James’s Gate, dated from 1928 to 1955. There are plenty more books on Guinness I don’t have.

Despite all those volumes of Guinnessiana, however, you can still find a remarkable quantity of Guinness inaccuracy and mythology, constantly added to and recycled, particularly about the brewery’s earliest days. The myths and errors range from Arthur Guinness’s date of birth (the claim that he was born on September 24, 1725 is demonstrably wrong) to the alleged uniqueness of Guinness’s yeast: the idea that the brewery’s success was down to the yeast Arthur Guinness brought with him to Dublin is strangely persistent, though the brewery’s own records show that as early as 1810-12 (and almost certainly earlier) St James’s Gate was borrowing yeast from seven different breweries.

Most accounts of the history of Guinness also miss out on some cracking stories too little known: the homosexual affair that almost brought the end of the brewery partnership in the late 1830s, for example; the still-unexplained attack of insanity that saw Guinness’s managing director, great-great nephew of Arthur Guinness I, carried out of the brewery in a straitjacket in 1895; and the link between the writings of Arthur Guinness I’s grandson Henry Grattan Guinness and the foundation of the state of Israel (which takes in the assassination of Arthur Guinness I’s great-great grandson in Egypt).

![Guinness WI Porter Liverpool Mercury Guinness WI Porter ad Liverpool Mercury 1819]()

An advertisement for one-year-old West India porter from 1819

Let’s deal with a few more myths first, before we get into the juicy stuff. All the below are to be found in a book published in 2009 called Guinness: An Official Celebration, with a foreword by Rory Guinness, five-greats grandson of Arthur I:

1) “Arthur Guinness was born in 1725 in Celbridge, County Kildare.” The Dictionary of Irish Biography claims he was born on March 12 1725. However, that does not match the statement on Arthur Guinness’s grave in Oughterard, Kildare that he died on January 23 1803 “aged 78 years”, from which it can be inferred that his birthday must have been between January 24 1724 and January 23 1725. The most accurate statement, therefore is that his date of birth is unknown, but he was born 1724/5

2) “His father, Richard Guinness, was land steward to the Reverend Arthur Price, later Archbishop of Cashel, and his duties included brewing for the workers on the Archbishop’s estate.” There is NO evidence that Richard Guinness brewed for Archbishop Price, and it’s not usually, I suggest, the sort of task the land steward would have done anyway. Many narratives go on to claim that Arthur learnt to brew from helping his father. While it isn’t impossible that Arthur Guinness might have done some brewing or assisted with some brewing at Price’s estate, Bishopscourt – large domestic and farming establishments were somewhere between quite and highly likely to have their own brewing operation to supply ale for the farmworkers, the household servants and even the family – the brewing seems more likely, on the little evidence we have from elsewhere, to have been done by one of the lowlier servants, rather than the sort of educated young man Arthur Guinness obviously was.

(There are also regularly recurring claims that Arthur Guinness, or his father, was already brewing a black porter-like beer for Archbishop Price, which since we know his breweries at Leixlip and St James’ Gate originally only made ale, is another example of people Making It Up.)

3) “In 1752 the Archbishop died and bequeathed Arthur Guinness the sum of £100. Arthur used the money to open a small brewery in Leixlip.” While Price did leave Arthur (and his father Richard) £100 each in his will, this £100 was NOT the money that enabled Arthur to buy the brewery in Leixlip in 1755. As Patrick Guinness’s excellent book on the early years of the brewery, Arthur’s Round, makes clear, the money Arthur used to start in business as a brewer three years after the Archbishop’s death must largely have come from his father’s savings over 30 years of employment with Archbishop Price, plus, perhaps, money Richard had made from three years of running the White Hart inn in Celbridge after Price’s death.

![Guinness ad Bristol Mercury 1825 Mild Stout - put that in your styleguides]()

An ad for extra-superior porter and ‘mild-stout Porter’, the latter strong but unaged

4) “Guinness was brewed using roasted barley, which gave it a distinct dark colour and taste.” Using unmalted barley, roasted or otherwise, was illegal when Arthur began brewing porter and stout, and roasted barley only started being used by Guinness around 1929/1930.

5) “Arthur Guinness must have been very confident that his beer would be a success as he signed a 9,000-year lease on the brewery.” This was almost certainly a legal fix to avoid, for whatever reason, a full transfer of the freehold, rather than any sign of confidence.

![Arthur Lee Guinness]()

Arthur Lee Guinness

And now, a scandal or two. In 1839 Arthur Guinness II, the son of the founder, who had run the brewery since before his father’s death in 1803, was now in his 70s, and withdrawing from the business to leave it in the hands of the third generation. Arthur II had married Anne Lee in 1793. His eldest son, William, had entered the Church, and the two younger sons, Arthur Lee Guinness and Benjamin Lee Guinness, had been brought up to run the brewery. Benjamin had become a partner when he was 22, Arthur when he was 23. However, Arthur Lee became snared in a scandal that came close to seeing the business wound up.

Arthur Lee Guinness was living unmarried at the age of 42 in an apartment at the St James’s Gate brewery. He wrote nature poetry, collected pictures and sealed his letters with a stamp showing a young Greek god. His apartment was described by an American relative in 1840 as “crowded with knick-knacks, statuary, paintings, stuffed birds etc. His drawing room is furnished in Chinese style and most richly. In the yard there are plenty of gods and goddesses etc. There is a fountain which plays into a willow tree …” It was hardly the conventional lifestyle of a middle-aged brewer.

In the spring of 1839 the brewery hired as a clerk an 18-year-old would-be actor, Dionysius Boursiquot, the son of a Guinness relative-by marriage, Anna Maria Darley. Dionysius’s father was almost certainly a Trinity College lecturer and engineer, Dionysius Lardner (who is now making his second appearance in this blog), rather than Anna Darley’s husband, the Dublin wine merchant Samuel Boursiquot: Lardner had been their lodger. Dionysius Boursiquot, who later changed his name to Dion Boucicault and became a famous playwright and actor-manager, was slim and lively, with the dark hair and blue eyes typical of a certain type of Irish native – and Arthur Lee evidently became smitten.

Exactly what form the scandal took is unknown: the Guinness family seems to have removed all the records linked to it from St James’s Gate in the 1950s. But money was involved. Arthur Lee had apparently been issuing notes on the brewery partnership without the knowledge of the other partners, his father and brother. The obvious inference is that he was giving money to Boucicault, either as gifts or because he was being blackmailed.

A surviving letter in the Guinness archives from June 1839 from Arthur Lee Guinness to Arthur II shows clearly the pain he felt at his behaviour:

My dear Father, I well know it is impossible to justify to you my conduct if you will forgive me it is much to ask, but I already feel you have & I will ever be sincerely grateful … I know not what I should say, but do my dear Father believe me I feel deeply … the extreem [sic] & undeserved kindness you have ever, and now, More than ever shown me.

Believe me above all that ‘for worlds’ I would not hurt your mind, if I could avoid it – of all the living. Your feelings are most sacred to me, this situation, in which I have placed myself, has long caused me the acutest pain & your wishes on the subject must be religiously obeyed by me. I only implore you to allow me to hope and forbear a little longer, I feel it but just to do so …

Your dutiful, grateful but distressed son

A.L.G.

It appears that Boucicault was paid to go away: he turned up in London in May 1840 with enough money to buy a horse and carriage and entertain his friends “lavishly”. Meanwhile Arthur II and Benjamin agreed with Arthur Lee’s suggestion that, as part of the resolution of the crisis, he leave the brewery partnership, taking enough cash out of the business, £12,000, to buy his own home, Stillorgan Park, south of Dublin, and live “moderately”. Surviving letters in the Guinness archive indicate that at one point during the crisis it was suggested the whole brewing concern should be “given up” on the dissolution of the partnership between Arthur II and his sons. This would have meant the end of Guinness. However, a new partnership was formed without Arthur Lee, but with his father as titular head and his brother Benjamin at the helm, assisted by another partner, the son of the former brewery head clerk, John Purser junior.

![Guinness visitors' train 1928 Love that hat]()

The train that took visitors around St James’s Gate in the 1920s

Arthur Lee Guinness’s life after he left the brewery was not that moderate: another American visitor, Amelia Ransome Neville, described Stillorgan Park in the 1850s as “the most enchanting home I have ever known,” filled with embroidered silks, ivories, carved teak, and bronze gods. Arthur Lee organised weekend parties where guests included the Duke of Leinster and the Earl of Clarendon. Every afternoon at Stillorgan Park, Amelia wrote, “a blind harper, with white beard and flowing white hair, sat over at one side of the court and sang old melodies while he played an Irish harp.”

An English visitor in 1853 called Stillorgan Park “a veritable showplace. One saw there a superb house, elegantly furnished, with costly conservatories and gardens about, filled with the rarest flowers, and well-kept lawns and parks with paths through overshading trees, while statuary peeped out from clumps of thickest shrubbery a beautiful demesne indeed with outspread signs on every side of its owner’s wealth.” One of Arthur Lee’s cousin’s, Eliza O’Grady, lived with him at Stillorgan Park, doubtless playing the part of hostess.

Arthur Lee left Stillorgan Park in 1860, dying three years later, aged 65, at his final home, Roundwood House, Wicklow. While the sale of the contents of Stillorgan Park was taking place in 1860, Arthur Lee had a harper in the grounds play funeral dirges. The first Guinness bottle labels bearing the now famous harp trademark were issued in August 1862. We must wonder if Arthur Lee’s obvious fondness for harpers influenced the company’s choice of logo.

![Guinness from the air 1939 Guinness from the air 1939]()

The St James’s Gate brewery from the air in 1939

By the early 1880s the brewery was being run by Arthur Lee’s nephew, Edward Guinness. But Edward, although only in his mid 30s, was slowly moving towards disentangling himself from the business. In 1873 he had married a distant cousin, Adelaide Guinness, who was the great-granddaughter of Arthur Guinness I’s brother Samuel. With his eldest son still a child, Edward had apparently solved the problem of maintaining family control by bringing in his wife’s youngest brother, Claude Guinness, as a senior manager in 1881. Claude was 29, he had graduated from New College, Oxford with a first-class degree, and he possessed a natural business brain. Now Edward could find the time to use his wealth in the pursuit of leisure. In 1880 he took a three-year lease on a Scottish grouse moor, an excellent excuse to extend hospitality to the socially influential. In 1882 he bought a schooner from the Earl of Gosford, a good friend of the Prince of Wales, which brought him into the yachting set that surrounded the future Edward VII.

In 1890, three years after the brewery had been floated as a public company, Edward Guinness left the Guinness board. Claude, 38, was managing director, with his older brother Reginald 48, now chairman. Later that year Edward was granted the title he longed for, becoming Lord Iveagh. In 1894 he acquired the stately home to go with the title, buying Elveden Hall in Suffolk for £159,000, the equivalent of £6 million in early 21st century money.

Edward’s plan to leave the daily concerns of St James’s Gate to his wife’s brothers and immerse himself completely in the golden life of an English aristocrat began to be derailed almost as soon as he acquired Elveden Hall. One day early in 1895 the brilliant Claude Guinness had a complete mental breakdown while working at St James’s Gate, and had to be removed from the brewery in a straitjacket. The trauma of the managing director being carried off raving was so great, somebody tore out the relevant page in the daily brewery log. There were rumours in the Guinness family much later that it was General Paralysis of the Insane – dementia brought on by the final stages of syphilis – and Claude was dead within a few weeks, aged 43. However, there is no other evidence to support this diagnosis: he had two healthy daughters, born 1891 and 1893 who, if he HAD been suffering from syphilis, would have been expected to show symptoms themselves. His sister Adelaide, Edward’s wife, also suffered from dementia as she grew older, ending her years out of sight in a private wing at Elveden Hall.

![Guinness coppers 1939 Coppers at St James's Gate 1939]()

Coppers at the St James’s Gate brewery, 1939

Reginald Guinness, who had only reluctantly become chairman in 1890, now had to become managing director as well. In 1897 Edward rejoined the company board, and when Reginald retired in 1902 aged 60, Edward took back the chairman’s role, though 55 himself. He remained in control until his death in 1927 aged 80. It has been suggested that Claude’s death, by bringing Edward back to be in ultimate charge of the company for so long, prevented Guinness from reacting appropriately to the difficulties it faced after the First World War, with product quality problems and declining demand for its beer.

While Edward Guinness was helping to make the family synonymous with stout, another branch was bringing the Guinness name to the attention of the public in a completely different field: Biblical Zionism. Henry Grattan Guinness, son of Arthur Guinness I’s youngest brother, John Grattan Guinness, had been born in 1835, became an evangelical preacher in his 20s and, like his uncle Hosea, Arthur’s oldest son, had been ordained a minister. Henry worked among the poor in the East End of London, but also turning himself into an expert in “Biblical prophecy”.

In books such as The Approaching End of the Age, which sold 15,000 copies in eight years, and Light for the Last Days (1888), Henry told the world that the Bible showed the “times of the Gentiles” was coming to an end, which would be marked by the return of the Jews to their homeland in Palestine. Using figures obtained from the Old Testament, which he linked to astronomical observations, Henry predicted in Light for the Last Days that a key year in this eventual return would be 1917.

Among the people who read Henry Grattan’s analyses of history as seen through the prism of Biblical prophecy was Arthur Balfour, who wrote to Henry in 1903, when he was prime minister, to say that he was very interested in Henry’s books and had studied them closely. Henry died in 1910, but in November 1917, Balfour, then foreign minister, signed what became known as the Balfour Declaration, a letter to Lord Rothschild which declared that the British government would use its “best endeavours” to facilitate the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.

Did Balfour act deliberately to bring Henry Grattan’s prophecy to pass? He certainly must have issued the declaration knowing what Henry Grattan had said about 1917. However, late 1917 was strategically probably the first and best time such a declaration could have been made by Britain anyway: the Allied armies had finally begun to overcome the Germans and Turks in the war in Palestine. Five weeks after the Balfour Declaration was issued, Sir Edmund Allenby’s troops liberated Jerusalem.

Whatever Henry Grattan’s influence on the Balfour Declaration, Britain initially encouraged Jewish immigration into Palestine, under its post-First World War League of Nations Mandate to govern the territory. After the Arabs living in Palestine eventually broke out in revolt in the 1930s over the continuing arrival of Jewish settlers, Britain tried to curtail the number of Jews allowed in. During the Second World War, the restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine remained in place, a policy that caused increasing anger among Jewish militants in the territory.

![Storage vats Guinness 1939 Storage vats Guinness 1939]()

Giant storage vats, some 24 feet high, at the Guinness brewery in 1939

In November 1944, as part of a terrorist campaign directed at trying to get those restrictions lifted, two members of a Jewish group known to the British authorities as the Stern Gang shot dead in Cairo the British Minister Resident in the Middle East – Walter Guinness, Lord Moyne, Ernest Guinness’s third son, and Henry Grattan Guinness’s first cousin twice removed. If Henry did inspire the Balfour Declaration with his predictions, then, arguably, he set off a chain of dominoes that resulted, 56 years later, in his father’s brother’s great-grandson getting hit by three revolver bullets as he sat in the front passenger seat of his black Humber limousine waiting to be let into his official residence after a trip to the British Embassy in Cairo.

(Incidentally, in The Search for God and Guinness, published 2009, Stephen Mansfield claims that “Henry Grattan Guinness, writing nearly sixty years before the event, predicted the miraculous event of 1948 [the declaration of the founding of the State of Israel] when Israel again became a nation. This remains one of the most prescient works of an author in history.” I am not aware, however, that Henry Grattan ever referred to 1948 in connection with Israel in any published work: this appears to be another Guinness myth. The nearest we get to that claim is a note by Michele Guinness in her book The Guinness Spirit that Henry had “scribbled in pencil” 1948 at the end of the final paragraph of the Book of Ezekiel in his “large black Bible”.

![Guinness cooperage yard Guinness cooperage yard]()

The cooperage yard at St James’s Gate in 1939

If all that has given you a thirst for more Guinness, here’s my personal list of the 10 best books about the brewery, its history, the family and the product:

1 The Guinnesses Joe Joyce 2009

Best general study of the brewery and the family, reasonably free from error (though it gets the origins of porter wrong), and far fuller than most on events such as the Arthur Lee scandal: Joyce has a journalist’s eye for a good story, and excellent command of a multi-stranded narrative.

2 Arthur’s Round Patrick Guinness 2008

The essential antidote to many Guinness myths and misunderstandings, and the most in-depth study of Arthur Guinness I’s roots and the early years of the enterprise.

3= Guinness’s Brewery in the Irish Economy 1759-1876 Patrick Lynch and John Vaizey 1960

3= Guinness 1886-1939: From Incorporation to the Second World War SR Denison and Oliver MacDonagh 1998

(only two thirds of the original manuscript, which sits in the Guinness Archives)

Two of the best business history books on any subject, and essential if you want to understand the growth and expansion of the company. Pity about the 10-year gap in coverage between 1877 and 1885 …

5 A Bottle of Guinness Please David Hughes 2008

Primarily meant to be a history of Guinness bottling and exporting, but fabulously detailed on everything from the brewing process to the label printing, and superbly illustrated. Major flaw – no index

6 The Book of Guinness Advertising Jim Davies 1998

13 years later, and therefore more up to date, that the identically titled and also excellent book by Brian Sibley. Guinness porn. Unfortunately now 14 years out of date, which means, for example, the Surfer ad from 1999, regarded as one of the greatest advertisements ever made, is missing.

7 The Guinness Book of Guinness Edward Guinness 1988

Massive collection (540 pages) of anecdotes covering the first half-century of the Park Royal brewery, rammed full of fascinating stuff, such as the way the new brewery was “painted” with vat bottoms from St James’s Gate before it opened to try to ensure the same microflora and fauna were present and get the authentic Guinness flavour right. Major flaw – again, no index.

8 Requiem for a Family Business Jonathan Guinness 1997

A revealing study by the third Lord Moyne of the fading of family control of the firm, which culminated in the appointment of Ernest Saunders and the scandal of the dodgy dealings that went on in the Distillers takeover in 1987.

9 The Guinness Spirit Michele Guinness 1998

500-page volume by a Guinness-by-marriage on the whole family, not just brewers but bankers and missionaries, soldiers, politicians, socialites. Repeats a fair number of myths, but good for appreciating the evangelical strand that powered so many members of the Guinness family, and took them around the world, to China, to the Congo and to New Zealand, as well as the East End of London.

10 Guinness Times: My Days in the World’s Most Famous Brewery Al Byrne 1999

Al Byrne joined Guinness in 1938 aged 14 as a boy-labourer and rose through the ranks, working as a “number-taker” (recording the numbers and destinations of full casks as they left the brewery, and ticking them off when they returned) while, somehow, taking a degree at Trinity College, despite being a Roman Catholic. He graduated in 1945 and was immediately rewarded by Guinness with a staff job, unheard-of in the social conditions of the time. Later he worked as a “traveller” (sales rep) and in the internal communications department, producing the Guinness Times newspaper, before he left in 1978 to be a journalist. It’s an insightful view of conditions at the company over a period when it was starting to struggle, well produced and excellently illustrated.

There is still plenty more to be told about the history of Guinness that has not yet been revealed: I was lucky enough to get a day peeping into the archives at the Park Royal brewery in London before it closed, and there was masses of fascinating stuff, including a fair bit on the long, slow development of nitrogen-dispense draught Guinness, and all the technical problems that surfaced along the way. Must pull those notes out of the attic …

Filed under:

Beer,

Beer myths,

Brewery history ![]()

![]()

So hurrah, there’s now a group dedicated to pushing the message that British-brewed lager isn’t all Stella and Carling, they’re called Lager of the British Isles (LOBI – can’t decide if that’s creakingly bad or rather clever) and their website is here. You can also join them on Facebook, here. Maybe if LOBI lobbies hard enough, fewer people will drop their beerglasses like bystanders in a Bateman cartoon when they see the one the beer buff is holding has a lager in it.

So hurrah, there’s now a group dedicated to pushing the message that British-brewed lager isn’t all Stella and Carling, they’re called Lager of the British Isles (LOBI – can’t decide if that’s creakingly bad or rather clever) and their website is here. You can also join them on Facebook, here. Maybe if LOBI lobbies hard enough, fewer people will drop their beerglasses like bystanders in a Bateman cartoon when they see the one the beer buff is holding has a lager in it. By November 8 1871, however, the Hampshire Advertiser was announcing that the Anglo-Bavarian Brewery Company of Southampton had “recently purchased the new buildings in Shepton Mallet known as the Pale Ale Brewery, and are taking active steps to get their arrangements complete as early as possible … it is expected that by Christmas it will be in good working order.” The Advertiser expressed regret that the Anglo-Bavarian would be leaving the district: for the firm, which was run by a brewer called William Garton, had been brewing for at least a couple of years in Southampton, on a system using a form of invert sugar he had invented and which he called saccharum. Garton’s methods were designed to make ales “which possess all the essential properties of the highest class ales of Bavaria and Burton-on-Trent”. It brewed English ales, not Bavarian lagers, however. An ad for its “Anglo-Bavarian Ales” from the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle on March 27 1869 showed it was selling India Pale Ale, mild and strong ales, and amber ale. However, it had outgrown its Southampton site, where Garton also made saccharum for sale to other brewers, and acquired the Shepton Mallet premises to expand.

By November 8 1871, however, the Hampshire Advertiser was announcing that the Anglo-Bavarian Brewery Company of Southampton had “recently purchased the new buildings in Shepton Mallet known as the Pale Ale Brewery, and are taking active steps to get their arrangements complete as early as possible … it is expected that by Christmas it will be in good working order.” The Advertiser expressed regret that the Anglo-Bavarian would be leaving the district: for the firm, which was run by a brewer called William Garton, had been brewing for at least a couple of years in Southampton, on a system using a form of invert sugar he had invented and which he called saccharum. Garton’s methods were designed to make ales “which possess all the essential properties of the highest class ales of Bavaria and Burton-on-Trent”. It brewed English ales, not Bavarian lagers, however. An ad for its “Anglo-Bavarian Ales” from the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle on March 27 1869 showed it was selling India Pale Ale, mild and strong ales, and amber ale. However, it had outgrown its Southampton site, where Garton also made saccharum for sale to other brewers, and acquired the Shepton Mallet premises to expand. According to The Lancet, reviewing the company’s products in 1884, the Pilsner was “a light table ale”, the Bock and Munich “are akin to porter and stout”. The Lancet also revealed that the beers were available on draught, “aerated by a force pump, which brings it to the tap.” The Lancet liked the idea of lager being available in Britain: “considering its lightness and excellence, we are glad to see its popularity increasing so rapidly.” However, the “peculiar flavour” of the beers, The Lancet said, “compared by some to garlic and by others to curry, is, we believe, generated by the manufacture, and is liked by those who are used to it.”

According to The Lancet, reviewing the company’s products in 1884, the Pilsner was “a light table ale”, the Bock and Munich “are akin to porter and stout”. The Lancet also revealed that the beers were available on draught, “aerated by a force pump, which brings it to the tap.” The Lancet liked the idea of lager being available in Britain: “considering its lightness and excellence, we are glad to see its popularity increasing so rapidly.” However, the “peculiar flavour” of the beers, The Lancet said, “compared by some to garlic and by others to curry, is, we believe, generated by the manufacture, and is liked by those who are used to it.”